How To Become an Actor

If one thing is for certain when it comes to show business, the FNMI Workshops Charity believes there is more than one road to becoming an actor. Take Octavia Spencer, who spent years in minor and supporting roles before finding fame and an Oscar; or two-time Tony nominee Jonathan Groff, who booked his first national tour from a casting notice; or three-time Emmy winner Aaron Paul, who was “discovered” at an acting and modeling competition after moving from Idaho to Los Angeles.

If one thing is for certain when it comes to show business, the FNMI Workshops Charity believes there is more than one road to becoming an actor. Take Octavia Spencer, who spent years in minor and supporting roles before finding fame and an Oscar; or two-time Tony nominee Jonathan Groff, who booked his first national tour from a casting notice; or three-time Emmy winner Aaron Paul, who was “discovered” at an acting and modeling competition after moving from Idaho to Los Angeles.

These are just three of the countless different ways success can come your way as an actor—but when it comes knocking, you have to be prepared to give it all you’ve got. Below, we’ve rounded up everything you need to know about getting your foot in the door, whether that door leads to Hollywood, to Broadway, or anything in between.

There’s no one way to become an actor or actress. But these are the five most common steps for those pursuing a career path in show business:

Train to become an actor. There are no formal educational requirements for actors, but training is a good place to start. If you’re a student, consider getting a BFA or MFA in theater or attending summer programs; otherwise, local acting classes are the best choice for most people.

Patience and perspective if you’re going to make it as an actor. “Never, ever look to the prize,” Academy Award-winner Octavia Spencer says, “That’s something that you can’t control. What you can control is the work ethic and treating the material with respect. It took me 15 years to become an overnight success, so if you’re only at the three-year mark, honey, you’ve got some time.” So make sure that you can handle a long string of “no’s” before finally landing that coveted “yes.”

What are the different types of actors?

There’s a lot more to the industry than starring in the next Hollywood Blockbuster or Netflix Series. A helpful way to sort different types of acting opportunities is by Medium:

Screen Actors: Films, Television, Commercials & Web Series

Stage Actors: On-Broadway & Off-Broadway & Musical Theater

Voice Actors: Animation, Radio Ads, Podcasts, Video Games & Audiobooks

Your acting technique will vary depending on your medium. Acting for the camera is very different from acting for a live audience; doing commercial voiceover work will require different training than preparing for a musical theater audition. Of course, many actors move from stage to screen and back again through their career. But it may be helpful, as you begin your acting career, to consider which medium you’re most interested in.

Are there education requirements for actors?

No, there are no education requirements for actors—formal training can be helpful, but there are plenty of successful actors who never got an acting degree. That said, pretty much every actor working today has received some sort of training along the way.

But actor training can mean many things: there are acting and improv classes, BFA & MFA programs, on-set coaches, even online courses. Which option makes the most sense for you depends on several factors, including your age and experience level and whether you’re looking to make it on-stage or on-screen.

Acting Schools & Classes: Acting classes range widely in terms of content, time commitment, and price—making them the best option for most aspiring actors. Research what classes are offered in your city (you can use our Call Sheet or ask friends for references), audit a few promising options, then pick the teacher and technique that speaks to you. Then, stick with the class for at least six months. “If you love it, then continue, and when you can, add an improvisation and a commercial class or audition technique to see if you are interested in another area of acting,” says Expert Carolyne Barry.

How To Choose an Acting Class

Acting Coaches: Coaches are an important part of acting, but they’re not a stand-in for other training methods. Especially if you’re trying to get into acting with no experience, Expert Marci Liroff recommends starting with weekly classes. Acting coaches are better for fine-tuning, she notes—they won’t teach you the basics of movement and using your voice effectively.

Summer Training: If you’re a teen actor looking to sharpen your teeth with like-minded young talents, there’s no better place than summer training. There are several U.S. programs with a proven track record: The Atlantic Acting School (NYC) boasts such alums as Rose Byrne, Anna Chlumsky, and Matthew Fox, while Stagedoor Manor (Loch Sheldrake, N.Y.) counts Academy Award winner Natalie Portman, Robert Downey Jr., and Lea Michele among its alums.

Higher Education: A theater degree isn’t right for every actor. They can be incredibly expensive, and they’re never a guarantee of success. But a BFA or MFA can help you forge important connections, instill the value of hard work, and allow you to further hone your craft. Degrees can be particularly helpful if you want to become a stage actor.

If you’re trying to choose an undergraduate acting program, you’ll want to consider the pedigree of the program offered, the school’s location and its surrounding theater and talent pool, and who teaches and runs the program, among other things.

What do I need to start Auditioning for Roles?

Every actor needs at least three things when trying to book an audition: headshots, an acting résumé, and a demo reel. Then, depending on your specialty, you may need additional materials—for instance, you’ll need to bring a book filled with cuts of various songs you’ve prepared if you’re auditioning for musical theater.

Headshot: A headshot is an 8” x 10” color photo of an actor from the chest up, with their face clearly visible. It will serve as your calling card for casting directors, talent agents, and anyone else deciding whether or not to give you a shot. Headshots are the foundation of your marketing materials—and, ultimately, your personal brand—which means there’s a lot riding on a few photos. Our in-depth guide will walk you through everything you need to know about headshots, from pricing to posing to retouching.

Acting Résumé: Like traditional résumés, acting résumés should be one page long and summarize your relevant experience. More specifically, acting résumés should include:

Acting Credits

Special Skills (Accents, Martial Arts, Boxing, Pro Wrestling, Horseback Riding, Musical Instruments, etc.)

You’ll want to break up your acting credits by type. Categories are often listed as follows: Film/TV, Commercials/Industrials, Broadway, National Tours, Regional Theater, Academic Theater, Training/Degrees, and Special Skills. All credits should include show titles, roles, directors, and producing organizations—casting directors are known to give directors or producing companies a call for feedback. Physical attributes like weight, height, and hair and eye color should be included for film productions (especially if you’re self-taping), while theater auditions usually don’t require such details.

Above all, remember that acting résumés should be concise, clear, and easy to read. “Put yourself in the shoes of the person viewing it,” says actor David Patrick Green. “In most cases, they only have a few seconds to look at your material. If it is crowded and overwritten, it will be hard to latch onto what is relevant to their project.”

Demo Reel: Also known as a “sizzle reel,” a demo reel is a series of clips that showcase your previous acting credits; it can also include footage of you acting out a scene or monologue specifically for that reel. Reels are generally two minutes long, with each clip lasting 20-30 seconds. Casting directors, agents, and producers use reels to decide whether or not they will ask an actor in for an audition—so it’s essential that you present yourself in the best possible light. For a more detailed breakdown of the process, check out our guide to demo reels.

How do I find Acting Auditions & Casting Calls?

Most early-career actors don’t have managers or agents who are in direct contact with casting directors, which means it’s up to you to find auditions. Luckily, the internet has made things a lot easier—online casting platforms like ours are home to thousands of vetted casting opportunities that are updated daily. These range from smaller projects like student shorts, web series, and regional theater productions to larger Hollywood features and productions on the Broadway stage. These casting notices are key to building up your demo reel.

What should I expect at an acting audition?

The key to any audition is preparation. That means knowing the ins and outs of the project you’re auditioning for and knowing the context of the scene that you’re auditioning with. That means having your 16 bars for a musical theater audition down pat and your voice warmed up and ready to belt. That means having your sides memorized and being open to criticism or edits from those you’re auditioning for. It also means entering the room feeling confident that this is the role for you, nerves be damned! Desperation shows, and it won’t do you any favors when it comes to casting out roles.

Of course, that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Auditioning is a huge part of becoming a successful actor—which is why we put together an in-depth guide to the process. We walk you through the nitty-gritty details, like what to wear and how to create a self-tape, plus the specifics of different types of auditions, from TV to theater to commercials.

How do I get an acting agent?

Actors who are just starting out are often in a rush to find representation—but the truth is, you don’t need an agent at the very beginning of your career. Plus, most agents just aren’t interested in repping an actor with zero professional experience! Before you start reaching out to talent agencies, you’ll likely need to spend a minimum of one year training with qualified teachers, putting together a quality demo reel, and forging connections across the industry. (This checklist may be helpful in determining whether or not you’re reading to start your search for a talent agent.)

Once you’ve built up your résumé, it’s time to do your research. To successfully land an acting agent, you need to figure out which agencies make sense for your career goals. Some agents specialize in theater, others in TV. Figure out which agents rep actors with careers or types similar to yours. You’ll need to submit by sending them a cover letter, headshots, and résumé. Referrals are even better. For more tips on how to navigate this process, our guide to securing an acting agent goes through everything from nailing your first agent meeting to the telltale signs of a bad agent.

Where is the best place to live as an actor?

The first question that many young actors find themselves pondering is if (and when) they should move to New York or Los Angeles. NYC and L.A. are two of the largest markets for working actors today—but which one is right for your career depends on what roles you’re hoping to land. Do you want to star in mainstream film and TV? Los Angeles is probably your best bet. For Broadway and all things theater, New York has you covered. There are exceptions to that rule, of course—TV and film projects work out of New York all the time, and L.A. has theater—but opportunities will be more limited.

That said, relocating to a major market at the start of your career isn’t necessarily the best move. It’s no secret that these cities aren’t cheap. In fact, it’s due to the high costs of L.A. & NYC that many film and TV projects have transferred their productions to markets like Atlanta and New Orleans. These cities are not only cheaper, but their states have implemented tax incentives for projects that choose to set up shop there.

In fact, Expert Todd Etelson recommends that you take advantage of regional markets. “If you’re willing to travel, there’s less competition in regional markets like Philadelphia, Washington, Richmond, etc. You’ll gain more auditions there and build your resume at a quicker pace.”

Any A-list actor will tell you that if you’re in the business to become famous, then it’s not the business for you. Not only is it the wrong approach to acting as a craft, it will also (most likely) prove futile. The top-tier actors you see on the covers of magazines got there after years of training and years of rejection. They’ve shown charisma and warmth when interacting with the media and with their audiences. They’ve gained the respect of their peers and of their colleagues in agencies and casting offices throughout the industry. Simply put: They’ve put the leg-work in.

Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule. Social media, in particular, can sometimes serve as a shortcut to gaining visibility and fame. Catering your social media and your own look, type, and “brand” to what’s gaining traction in the industry is one way to expand your personal reach. Digital media outlets are another way to get eyes on you early in your career—and then it’s up to you to prove you’re worth the attention. It goes back to talent, training, and likability.

“Perhaps the easiest way to get discovered is to lose interest in discovery because you’re so profoundly in love with the art of acting, doing it for its own sake,” say Experts Rita Bramon Garcia and Steve Braun. “When you lose yourself in it, focus on each glorious moment as opposed to the end game, and do the work of falling in love with acting, discovery comes.”

Actors are performing artists who portray characters on stage and in television shows, commercials, movies, and shows at amusement parks. While it is not a gender-specific term—both males and females in this occupation are called “actors”— the word “actor” is often used when talking about a male while “actress” is used to describe a female.

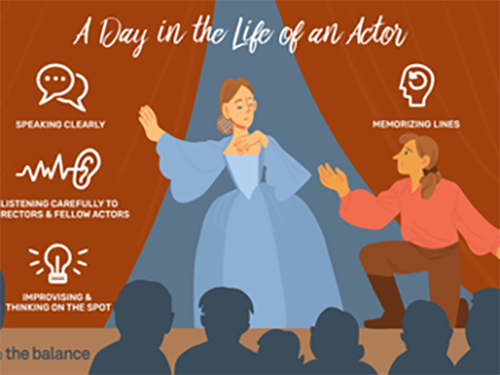

Actor Duties & Responsibilities

This job generally requires the ability to do the following work:

- Read Scripts

- Rehearse Scenes

- Exhibit Broad Ranges of Emotions on Cue

- Improvise

- Memorize Lines

- Research Characters

- Follow Directions

- Go on Auditions

Actors are artists, but the art is made up of many smaller skills that can be learned and practiced. Like many trades, preparation is a big part of success. To really embody a role and convince a casting agent that they are right for the part, actors need to study the characters they hope to portray. This is more than just reading the script and memorizing lines. It’s about understanding what motivates a character and why a character behaves in a certain way.

This preparation and the resulting performances in auditions are just part of the job. Actors also must work with an agent at finding the right roles and opportunities. And when actors finally do land a job, they need the skills to be able to collaborate effectively with fellow actors, the director, and other members of the crew.

Education, Training & Certification

Actors typically need some kind of formal education, whether it be a degree in theater or drama or regular acting classes. Training in other areas relative to performing also is beneficial.

Education: Formal training doesn’t necessarily mean college. A bachelor’s degree in theater or drama is one option, but acting or film classes at a community college, theater company’s acting conservatory, or film school also is a good option for some actors.

Training: In addition to gaining acting experience, it’s beneficial for actors to be trained in skills that can be useful. These can include singing or other vocal training, dance lessons, martial arts, and much more. Having the right skills is what sometimes gets actors in the door for an audition.

Actor Skills & Competencies

Acting is both a skill and an art and being good at it requires some soft skills that can help make performances seem as real as possible.

Active Listening: Actors need to be able to respond to other actors in the moment, while in character. They also need to respond to what a director wants.

Verbal Communication: Acting involves collaborating, and that sometimes means conveying to others details about a scene or a performance. From a practical standpoint, actors also need to be able to enunciate clearly so other actors and audience members can hear them and understand them clearly.

Creativity: Writers might have an idea for what a character should be, but actors need to bring it to life. To find what motivates a character, actors sometimes need to come up with a backstory, if only for their own benefit.

Memorization: Actors must be able to memorize lines.

Persistence: This is a competitive field, and actors have to repeatedly audition and deal with rejection.

Job Outlook

Jobs for actors are projected to grow at 12 percent for the decade ending in 2026, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is significantly better than the 7 percent growth projected for all occupations.

Film actors are expected to see much better growth than theater actors.

Work Environment

Work environments can vary greatly. Working on stage is different from working in front of a camera, and actors working in front of a camera might be in a studio or on location in extreme weather. Some actors might work in other environments, such as theme parks or other themed attractions that include characters. Actors need to be able to collaborate effectively with other actors, directors, and various members of a shoot or production.

Work Schedule

Actors only work full time if they have a regular role in a television show or are part of a long-running stage production. When they are working, actors’ schedules can be unpredictable depending on shooting schedules. Long days are common, and it’s not unusual for films and television shows to shoot at all hours depending on the needs of a scene.

How to Get the Job!

WORK

Even the smallest role in a community theater production is better than sitting at home by the phone.

BE PERSISTENT

Expect rejection. Learn from it, but don’t dwell on it.

Comparing Similar Jobs

People interested in acting also might consider one of the following career paths:

- Announcer: $30,000 – 60,000 a Year

- Film & Video Editor: $60,000 – 80,000 a Year

- Producer or Director: $70,000 – 90,000 a Year

Let’s Talk Acting

Acting is an activity in which a story is told by means of its enactment by an actor or actress who adopts a character—in theatre, television, film, radio, or any other medium that makes use of the mimetic mode.

Acting involves a broad range of skills, including a well-developed imagination, emotional facility, physical expressivity, vocal projection, clarity of speech, and the ability to interpret drama.

Acting also demands an ability to employ dialects, accents, improvisation, observation and emulation, mime, and stage combat.

Many actors train at length in specialist programs or colleges to develop these skills. The vast majority of professional actors have undergone extensive training.

Actors and actresses will often have many instructors and teachers for a full range of training involving singing, scene-work, audition techniques, and acting for camera.

Most early sources in the West that examine the art of acting (Greek: ὑπόκρισις, hypokrisis) discuss it as part of rhetoric.[1]

Let’s Talk History

One of the first known actors was an ancient Greek called Thespis of Icaria in Athens. Writing two centuries after the event, Aristotle in his Poetics (c. 335 BCE) suggests that Thespis stepped out of the dithyrambic chorus and addressed it as a separate character. Before Thespis, the chorus narrated (for example, “Dionysus did this, Dionysus said that”).

When Thespis stepped out from the chorus, he spoke as if he was the character (for example, “I am Dionysus, I did this”). To distinguish between these different modes of storytelling—enactment and narration—Aristotle uses the terms “mimesis” (via enactment) and “diegesis” (via narration). From Thespis’ name derives the word “thespian”.

Let’s Talk Training

Stanislavski began to develop his ‘system’ of actor training, which forms the basis for most professional training in the West.

Conservatories and drama schools typically offer two- to four-year training on all aspects of acting. Universities mostly offer three- to four-year programs, in which a student is often able to choose to focus on acting, whilst continuing to learn about other aspects of theatre. Schools vary in their approach, but in North America the most popular method taught derives from the ‘system’ of Konstantin Stanislavski, which was developed and popularised in America as method acting by Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Sanford Meisner, and others.

Other approaches may include a more physically based orientation, such as that promoted by theatre practitioners as diverse as Anne Bogart, Jacques Lecoq, Jerzy Grotowski, or Vsevolod Meyerhold. Classes may also include psychotechnique, mask work, physical theatre, improvisation, and acting for camera.

Regardless of a school’s approach, students should expect intensive training in textual interpretation, voice, and movement. Applications to drama programs and conservatories usually involve extensive auditions. Training may also start at a very young age. These classes introduce young actors to different aspects of acting and theatre, including scene study.

Increased training and exposure to public speaking allows humans to maintain calmer and more relaxed physiologically. By measuring a public speaker’s heart rate maybe one of the easiest ways to judge shifts in stress as the heart rate increases with anxiety . As actors increase performances, heart rate and other evidence of stress can decrease. This is very important in training for actors, as adaptive strategies gained from increased exposure to public speaking can regulate implicit and explicit anxiety. By attending an institution with a specialization in acting, increased opportunity to act will lead to more relaxed physiology and decrease in stress and its effects on the body.

Let’s Talk Improvisation

Two masked characters from the commedia dell’arte, whose “lazzi” involved a significant degree of improvisation.

Some classical forms of acting involve a substantial element of improvised performance. Most notable is its use by the troupes of the commedia dell’arte, a form of masked comedy that originated in Italy.

Improvisation as an approach to acting formed an important part of the Russian theatre practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski’s ‘system’ of actor training, which he developed from the 1910s onwards. Late in 1910, the playwright Maxim Gorky invited Stanislavski to join him in Capri, where they discussed training and Stanislavski’s emerging “grammar” of acting.

Inspired by a popular theatre performance in Naples that utilized the techniques of the commedia dell’arte, Gorky suggested that they form a company, modeled on the medieval strolling players, in which a playwright and group of young actors would devise new plays together by means of improvisation. Stanislavski would develop this use of improvisation in his work with his First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre. Stanislavski’s use was extended further in the approaches to acting developed by his students, Michael Chekhov and Maria Knebel.

In the United Kingdom, the use of improvisation was pioneered by Joan Littlewood from the 1930s onwards and, later, by Keith Johnstone and Clive Barker. In the United States, it was promoted by Viola Spolin, after working with Neva Boyd at a Hull House in Chicago, Illinois (Spolin was Boyd’s student from 1924 to 1927).

Like the British practitioners, Spolin felt that playing games was a useful means of training actors and helped to improve an actor’s performance. With improvisation, she argued, people may find expressive freedom, since they do not know how an improvised situation will turn out. Improvisation demands an open mind in order to maintain spontaneity, rather than pre-planning a response.

A character is created by the actor, often without reference to a dramatic text, and a drama is developed out of the spontaneous interactions with other actors. This approach to creating new drama has been developed most substantially by the British filmmaker Mike Leigh, in films such as Secrets & Lies (1996), Vera Drake (2004), Another Year (2010), and Mr. Turner (2014).

Improvisation is also used to cover up if an actor or actress makes a mistake.

Let’s Talk Physiological Effects

Speaking or acting in front of an audience is a stressful situation, which causes an increased heart rate.

In a 2017 study on American university students, actors of various experience levels all showed similarly elevated heart rates throughout their performances; this agrees with previous studies on professional and amateur actors’ heart rates. While all actors experienced stress, causing elevated heart rate, the more experienced actors displayed less heart rate variability than the less experienced actors in the same play.

The more experienced actors experienced less stress while performing, and therefore had a smaller degree of variability than the less experienced, more stressed actors. The more experienced an actor is, the more stable their heart rate will be while performing, but will still experience elevated heart rates.

Let’s Talk Semiotics

Antonin Artaud compared the effect of an actor’s performance on an audience in his “Theatre of Cruelty” with the way in which a snake charmer affects snakes.

The semiotics of acting involves a study of the ways in which aspects of a performance come to operate for its audience as signs. This process largely involves the production of meaning, whereby elements of an actor’s performance acquire significance, both within the broader context of the dramatic action and in the relations each establishes with the real world.

Following the ideas proposed by the Surrealist theorist Antonin Artaud, however, it may also be possible to understand communication with an audience that occurs ‘beneath’ significance and meaning (which the semiotician Félix Guattari described as a process involving the transmission of “a-signifying signs”).

In his The Theatre and its Double (1938), Artaud compared this interaction to the way in which a snake charmer communicates with a snake, a process which he identified as “mimesis”—the same term that Aristotle in his Poetics (c. 335 BCE) used to describe the mode in which drama communicates its story, by virtue of its embodiment by the actor enacting it, as distinct from “diegesis”, or the way in which a narrator may describe it. These “vibrations” passing from the actor to the audience may not necessarily precipitate into significant elements as such (that is, consciously perceived “meanings”), but rather may operate by means of the circulation of “affects”.

The approach to acting adopted by other theatre practitioners involve varying degrees of concern with the semiotics of acting. Konstantin Stanislavski, for example, addresses the ways in which an actor, building on what he calls the “experiencing” of a role, should also shape and adjust a performance in order to support the overall significance of the drama—a process that he calls establishing the “perspective of the role”.

The semiotics of acting plays a far more central role in Bertolt Brecht’s epic theatre, in which an actor is concerned to bring out clearly the socio historical significance of behaviour and action by means of specific performance choices—a process that he describes as establishing the “not/but” element in a performed physical “gestus” within context of the play’s overal “Fabel”.

Eugenio Barba argues that actors ought not to concern themselves with the significance of their performance behaviour; this aspect is the responsibility, he claims, of the director, who weaves the signifying elements of an actor’s performance into the director’s dramaturgical “montage”.

The theatre semiotician Patrice Pavis, alluding to the contrast between Stanislavski’s ‘system’ and Brecht’s demonstrating performer—and, beyond that, to Denis Diderot’s foundational essay on the art of acting, Paradox of the Actor (c. 1770–78)—argues that:

Acting was long seen in terms of the actor’s sincerity or hypocrisy—should he believe in what he is saying and be moved by it, or should he distance himself and convey his role in a detached manner? The answer varies according to how one sees the effect to be produced in the audience and the social function of theatre.

Elements of a semiotics of acting include the actor’s gestures, facial expressions, intonation and other vocal qualities, rhythm, and the ways in which these aspects of an individual performance relate to the drama and the theatrical event (or film, television programme, or radio broadcast, each of which involves different semiotic systems) considered as a whole.

A semiotics of acting recognises that all forms of acting involve conventions and codes by means of which performance behaviour acquires significance—including those approaches, such as Stanislvaski’s or the closely related method acting developed in the United States, that offer themselves as “a natural kind of acting that can do without conventions and be received as self-evident and universal.” Pavis goes on to argue that:

Any acting is based on a codified system (even if the audience does not see it as such) of behaviour and actions that are considered to be believable and realistic or artificial and theatrical. To advocate the natural, the spontaneous, and the instinctive is only to attempt to produce natural effects, governed by an ideological code that determines, at a particular historical time, and for a given audience, what is natural and believable and what is declamatory and theatrical.

The conventions that govern acting in general are related to structured forms of play, which involve, in each specific experience, “rules of the game.” This aspect was first explored by Johan Huizinga (in Homo Ludens, 1938) and Roger Caillois (in Man, Play and Games, 1958).

Caillois, for example, distinguishes four aspects of play relevant to acting: mimesis (simulation), agon (conflict or competition), alea (chance), and illinx (vertigo, or “vertiginous psychological situations” involving the spectator’s identification or catharsis). This connection with play as an activity was first proposed by Aristotle in his Poetics, in which he defines the desire to imitate in play as an essential part of being human and our first means of learning as children:

For it is an instinct of human beings, from childhood, to engage in mimesis (indeed, this distinguishes them from other animals: man is the most mimetic of all, and it is through mimesis that he develops his earliest understanding); and equally natural that everyone enjoys mimetic objects.

This connection with play also informed the words used in English (as was the analogous case in many other European languages) for drama: the word “play” or “game” (translating the Anglo-Saxon plèga or Latin ludus) was the standard term used until William Shakespeare’s time for a dramatic entertainment—just as its creator was a “play-maker” rather than a “dramatist”, the person acting was known as a “player”, and, when in the Elizabethan era specific buildings for acting were built, they was known as “play-houses” rather than “theatres.”

Let’s Talk Resumes & Auditions

Actors and actresses need to make a resume when applying for roles. The acting resume is very different from a normal resume; it is generally shorter, with lists instead of paragraphs, and it should have a head shot on the back. Usually, a resume also contains a short 30 second to 1 minute reel about the person, so that the casting director can see your previous performances, if any.

Auditioning is the act of performing either a monologue or sides (lines for one character)[19] as sent by the casting director. Auditioning entails showing the actor’s skills to present themselves as a different person; it may be as brief as two minutes. For theater auditions it can be longer than two minutes, or they may perform more than one monologue, as each casting director can have different requirements for actors.

Actors should go to auditions dressed for the part, to make it easier for the casting director to visualize them as the character. For television or film they will have to undergo more than one audition. Oftentimes actors are called into another audition at the last minute, and are sent the sides either that morning or the night before. Auditioning can be a stressful part of acting, especially if one has not been trained to audition.

Let’s Talk Rehearsal

Rehearsal is a process in which actors prepare and practice a performance, exploring the vicissitudes of conflict between characters, testing specific actions in the scene, and finding means to convey a particular sense. Some actors continue to rehearse a scene throughout the run of a show in order to keep the scene fresh in their minds and exciting for the audience.

Let’s Talk Audience

A critical audience with evaluative spectators is known to induce stress on actors during performance, (see Bode & Brutten). Being in front of an audience sharing a story will makes the actors intensely vulnerable. Shockingly, an actor will typically rate the quality of their performance higher than their spectators.

Heart rates are generally always higher during a performance with an audience when compared to rehearsal, however what’s interesting is that this audience also seems to induce a higher quality of performance. Simply put, while public performances cause extremely high stress levels in actors (more so amateur ones), the stress actually improves the performance, supporting the idea of “positive stress in challenging situations”

Let’s Talk Heart rate

Depending on what an actor is doing, his or her heart rate will vary. This is the body’s way of responding to stress. Prior to a show one will see an increase in heart rate due to anxiety. While performing an actor has an increased sense of exposure which will increase performance anxiety and the associated physiological arousal, such as heart rate. Heart rates increases more during shows compared to rehearsals because of the increased pressure, which is due to the fact that a performance has a potentially greater impact on an actors career.

After the show a decrease in the heart rate due to the conclusion of the stress-inducing activity can be seen. Often the heart rate will return to normal after the show or performance is done; however, during the applause after the performance, there is a rapid spike in heart rate. This can be seen not only in actors but also with public speaking and musicians.

Let’s Talk Stress

There is a correlation between heart rate and stress when actors’ are performing in front of an audience. Actors claim that having an audience has no change in their stress level, but as soon as they come on stage their heart rate rises quickly. A 2017 University Study that looked at actors’ stress by measuring heart rate showed individual heart rates rose right before the performance began for those actors opening.

There are many factors that can add to an actors’ stress. For example, length of monologues, experience level, and actions done on stage including moving the set. Throughout the performance, heart rate rises the most before an actor is speaking. The stress and thus heart rate of the actor then drops significantly at the end of a monologue, big action scene, or performance.

Let’s Talk Demo Reels

To make a demo reel, you need four to five clips of your best on-screen performances. Each clip should be between 20-30 seconds long; the entire demo reel should be two to three minutes long, maximum. Your reel should also include your name, contact information, headshot, and website.

One to Two Minutes

One to two minutes long is the sweet spot for a demo reel. Aim to include three to five scenes that showcase both your comedic and dramatic chops. Lead with your most impressive credits. You never know when the viewer will stop watching, so place your most recognizable credits first.

Write a simple little dialogue scene that might last maybe. 30 seconds and just shoot that for the day and just use that in your demo reel it doesn’t have to be a big project.

Can a Demo Reel be a Monologue?

If you are brand new to acting and you are just starting to submit to projects, you may see that sometimes the breakdowns ask you to submit a demo reel. A 30-second acting clip of you doing a serious monologue or a funny monologue can showcase your Type, Voice, Expressions & Acting Level.

How do you make a Good Demo Reel?

- Keep it Short.

- Don’t Repeat Work.

- Frontload your Best Shots.

- Include only your Best Work.

- Include Breakdowns of Complex Shots.

- Add Text Labels to Explain Your Contribution.

- End with your Contact Details.

Now let’s look to the stars and make all our youth one of them.